MHM staff have been working tirelessly on creating not one, but two, new exhibition spaces: our core exhibition Everybody Had a Name and our youth- focused exhibition Hidden: Seven Children Saved

Not many will be aware of the intricacies involved in bringing a museum exhibition to life. From conceptualisation phases, artefact procurement, and importantly, working closely with survivors and their families to create an authentic experience, it truly is a momentous undertaking.

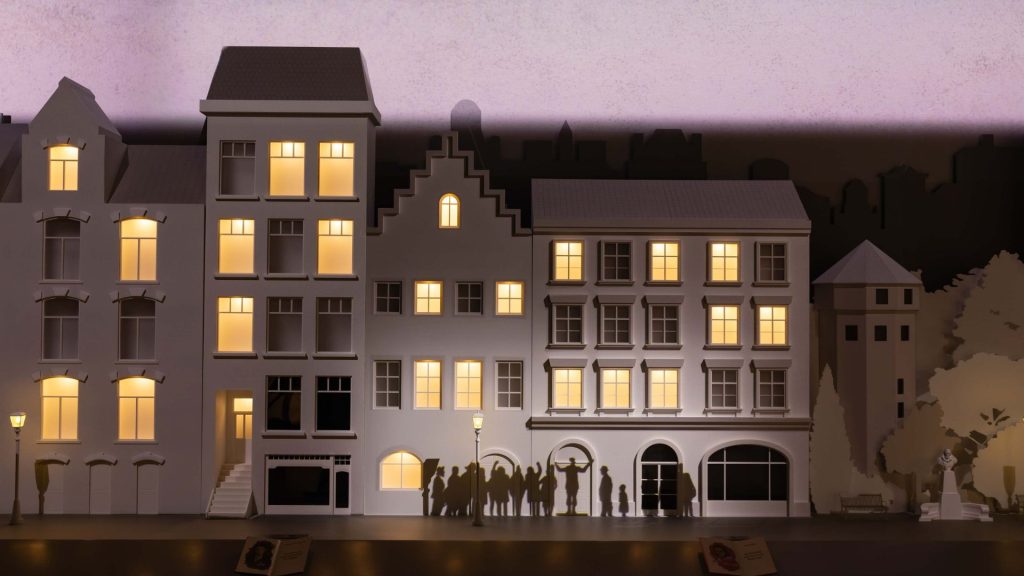

Everybody Had a Name is an exploration of the Jewish experience of the Holocaust, commencing with pre-war Jewish life, and concluding with how survivors rebuilt their lives in Melbourne.

Hidden: Seven Children Saved is an innovative exhibition designed to provide children aged 10 – 14 years old with a safe and meaningful interaction with the Holocaust, by following the experiences of one of seven child survivors who were in hiding during the war.

With MHM staff dedicating themselves to these thought- provoking, museum spaces over the past four years, they were thrilled to share their insights into the development process.