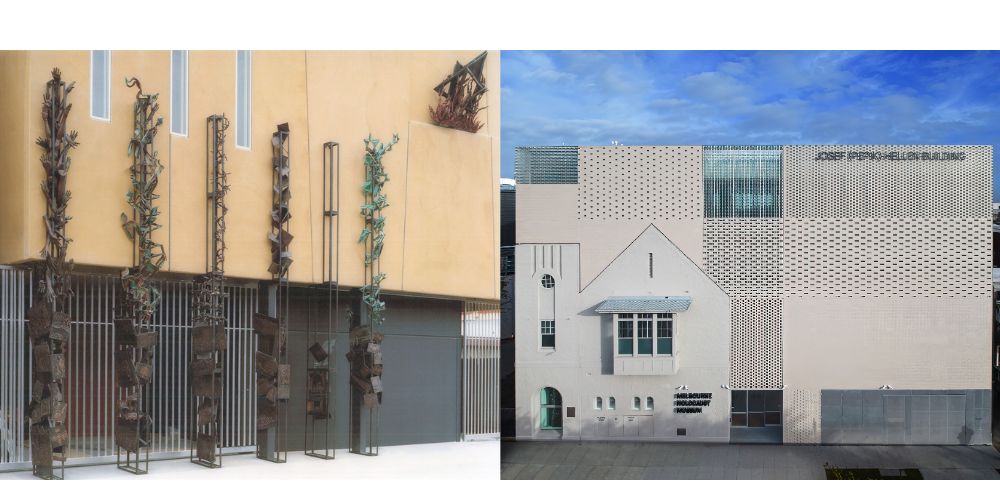

I was 19 years old when I first came to what was then known as the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) having read in the Jewish News that our community, the Melbourne Jewish community, was taking the initiative to open its own Holocaust museum in Selwyn Street, Elsternwick.

Historically, the creation of communal institutions is something that we, Jews, have excelled at. As soon as we arrive somewhere, no matter how few of us there are, we start the process of organising and building institutions to make things easier for those next to arrive. And we are always arriving somewhere because for thousands of years we have been continually fleeing something or someone.

The phenomenon that has led to our flight is what might be thought of as a social virus, an example of xenophobia par excellence, antisemitism, the negative discriminatory treatment of Jews as Jews on a factually unwarranted basis. It’s a virus that no society can ever quite entirely rid itself of, a societal illness that curiously, at least in its transmission and in its virulence, has nothing to do with us. Jews are not its cause. They are just the ones who suffer its consequences. It is its stubborn refusal to fade away, its ubiquitousness, and its quite astonishing capacity to adapt and bizarrely mutate, thriving in whatever circumstances currently prevail – permitting, for example, Jews to be seen simultaneously as seditious Bolsheviks and rapacious capitalists – that leads antisemitism, though an outstanding example of xenophobia, to be, in fact, a unique phenomenon in the psychopathology of the human species.

And all of this despite Jews constituting just 0.2% of the earth’s population. And the most extreme example of antisemitism in Jewish history is the Holocaust, the systematic attempt by Nazi Germany and its allies to annihilate the Jewish people, the historical event that this institution was created 40 years ago to commemorate and to educate people about.

So 40 years ago I rang around all my friends trying to find someone who would come with me to the opening, an event that would mark the beginning of my forty year and still ongoing relationship with this institution. I could not find anyone of my 19 and 20-year-old contemporaries to come with me. And I had gone to Mount Scopus. It was an incredibly hot March day radiating that almost white un-Ashkenazi light in which Australia specialises, a day that was closer to the end of the war than it is to now. I was shy around a community of survivors. I didn’t want anyone to think I was trying to co-opt my people’s tragedy for myself in some kind of self-indulgent adolescent way.

When I stood a few feet away from the survivor, Adek Bialik, when he collapsed in the hot sun and died, in a shocking example of tragic irony, I felt that maybe I shouldn’t have come, that perhaps this event belonged to an earlier generation. Why was I there, some 19-year-old interloper? My grandparents fled Poland and Russia before the Holocaust. They lost almost everybody they left behind but unlike so many Melbourne Jews of my generation, I didn’t have parents or even grandparents who were survivors.

I was an aspiring writer of fiction and after the opening of the museum I set myself the writing exercise of composing a short story about the experiences of a young Jewish man in 1980s Melbourne but in the style of the Yiddish master, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and it would include a fictionalised account of my experience of the opening of the MHM (as it is now known).

Would it be possible to write something set in contemporary Australia but in the style of I.B. Singer? It was the first adult short story I wrote, and I gave it the name, Spitalnic’s Last Year.

Fifteen years later, when it came time for my editors to choose stories from among the various stories I had thus far written for my forthcoming short story collection, The Reasons I Won’t Be Coming, this first story, Spitalnic’s Last Year, kept making the cut. But since I hadn’t known at the time of the opening of the museum that my experience of that day was going to inspire me to write a short story, or, indeed, to write anything at all, it’s still fair to ask what I was doing there. What made the 19-year-old me go there by myself that hot day? With the distance of forty years, I think I can now answer that. I was there because I was brought up to consider the events of those years to be, not simply the most important event in Jewish history, but perhaps the single most important measure of exactly what the human being is capable. If you really want to study the human being, you cannot do better than study the Holocaust.

Everything you need to know about humans you will find there; cruelty, savagery, the base use of ingenious technology, and of meticulous bureaucratic planning down to the tiniest detail for the sole purpose of mass murder, the sickening need of individuals to conform, the frighteningly limitless capacity for denial and for hypocrisy, but also the capacity for tenderness, kindness, bravery, the remarkable will to survive, and the stunning, breathtaking impulse to recreate – it’s all there.

And my upbringing had given me the compulsion then, as I was to write 30 years later in my novel, The Street Sweeper, to tell everyone what happened. It can often feel, especially recently, that the task of fighting antisemitism is so daunting as to be overwhelming and, as you’re assaulted by examples of it in your daily life, one simply doesn’t know where to start. From here it’s easy to fall prey to a paralysis of hopelessness and a kind of learned helplessness.

But it’s helpful to remember, first, that while antisemitism is sadly unlikely ever to be entirely eradicated, for diaspora Jews to be largely free of its very worst effects, it needs to be eradicated only to below a certain critical tipping point. From here it’s not impossible to imagine that under the right circumstances (these circumstances being perhaps better left for another essay) there could be a reduction of the viral load below antisemitism’s most dangerous tipping point. This really is achievable.