Having recently marked the 40th anniversary of the MHM in March, provides an opportunity to reflect not only on how we have developed as an organisation but also more broadly on the changes in Holocaust museums around the world. Although the opening of the then Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) in 1984 was one of several museums which started in the 1980s, the history of Holocaust museums and exhibitions of course goes back much earlier. Temporary exhibitions in camps like Buchenwald were held immediately after liberation, and the first wave of permanent Holocaust museums in Europe at sites of atrocity started in the decade following the end of the Second World War. Planning for what would become the Auschwitz State Museum started in 1946 for example. Away from the killing centres, the Memorial de la Shoah in Paris opened in 1956, while Yad Vashem was established in Jerusalem in 1957 (although both with antecedents much earlier).

Museums were also established far away from the Europe, such as the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust in 1961 and the Montreal Holocaust Museum in 1979. 1978 saw President Jimmy Carter establish the Commission on the Holocaust which led to the establishment of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1993. Although there were silences in families and in public discourse, this did not mean that the Holocaust had been forgotten: rather that memory took specific forms. Many survivors did talk and write about their experiences. In Melbourne for example, the first collection of written testimonies was published in Yiddish in 1946, and temporary exhibitions were held here in 1953, 1961, and 1980. Commemorative events were held yearly, including by individual Landsmanshaftn.

Museums were also established far away from the Europe, such as the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust in 1961 and the Montreal Holocaust Museum in 1979. 1978 saw President Jimmy Carter establish the Commission on the Holocaust which led to the establishment of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1993. Although there were silences in families and in public discourse, this did not mean that the Holocaust had been forgotten: rather that memory took specific forms. Many survivors did talk and write about their experiences. In Melbourne for example, the first collection of written testimonies was published in Yiddish in 1946, and temporary exhibitions were held here in 1953, 1961, and 1980. Commemorative events were held yearly, including by individual Landsmanshaftn.

Motivations for the establishment of the JHC in 1984, the first permanent Holocaust Museum in Australia, would be familiar to us today: the rise in antisemitism and racism, the need to educate future generations about the horrors of the Holocaust, and a need for a place where survivors could share their stories. Holocaust survivor, poet and philosopher Harry Redner wrote eloquently in the commemorative publication for the opening of the centre on what he termed an “ordinary suburban street”: it was a place to “show you what we have carried around for so long in silence and now have deposited in this unlikely place so that you, too, might if you so choose, care for these our mutual relics”.i For Redner this was an invitation to a shared ethics. Part of the urgency was a realisation on the part of the survivors who founded the JHC that they would not be around for ever to give their testimony. For co-founder Bono Wiener, the JHC “was started by his generation of survivors … [but] they would not be the ones to finish this important task”ii. Anxieties about the passing of the survivor generation have been with us since we began.

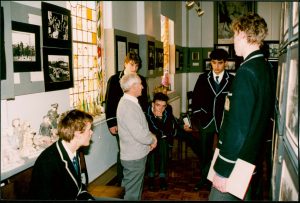

The JHC was, according to the late Helen Light, a heimishe or “homely” place. Over time, exhibitions were updated, the building changed, paid staff joined the volunteers, and survivors passed on the running of the organisation to others. However, they remained at the heart of the museum, either speaking to school groups, sitting on the board, providing wise counsel, and, in the case of the late Phillip Maisel OAM, running the testimonies project well into his 90s.

Changes of emphasis happened through the exhibitions too. Absent in the first iteration of the JHC exhibition in 1984 were displays related to the history of antisemitism, something that we would see as crucial today. Also missing were panels about survivors themselves. Their stories would filter through all of the displays and they would of course be present to speak to visitors directly about their experiences. The impact that survivors had in post war Australia has also grown over time in exhibitions. In part, temporary exhibitions at the JHC as well as permanent displays “To new life” provided a positive narrative of life in a new country: beginning again, starting families, building a home and a career. Obvious in the growing bank of testimonies collected by the JHC and in some of the artwork produced by survivors and displayed in the exhibitions was the ongoing trauma that, for many stayed with them. This has now found an explicit place in the core exhibit through Anita Lester’s powerful Noch Am Leben.

Holocaust museums and the MHM have also reflected and shaped changes in museum practice more generally. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the increasing importance of testimonies in our exhibitions, echoed by changes in historical practice more generally. From a suspicion of first-person accounts in academic history as subjective, the growth of social history and approaches to oral histories from the 1970s onwards gave increasingly legitimacy to individual’s narratives. Within the context of Holocaust testimony, not only did the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961 provide a high-profile platform for survivors to share their experiences, but major projects collecting survivor testimony began in the USA and in Australia in the 1970s and 1980s. We have seen the inclusion of testimony in the museum in different ways. With new technologies came new approaches. Digital technologies allowed the “Storypod” approach in the previous permanent display and now Virtual Reality means that we can “Walk with” the late John (Szaja) Chaskiel OAM on a journey through Poland and share from his perspective, what his family means to him now in Melbourne. We still have many survivors who generously share their time talking with school and other groups. But whilst we may no longer have Chaim Sztajer standing next to his Treblinka model in the museum talking to visitors about his experiences, we have his testimony both in audio-visual form and as embodied in the model itself and in the model of the Old Czestochowa Synagogue.

That there will soon be a Holocaust museum or education centre in every state and territory in Australia is a testament to the continuing importance of Holocaust education, remembrance, and research. Museums generally are increasingly globally connected with the ability to share information and network databases of collections and testimonies but also to shared “good practice”. Organisations such as the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) facilitate this exchange. Whilst there has been some concern that this might create a uniformity of approaches to memorial culture, what we are seeing is an increased emphasis on local stories and local connections to the Holocaust. Rather than the Holocaust being seen as long ago and far away, the experiences of the survivors who came to Australia and made their homes here, as well as the numerous other historical connections make the Holocaust a key part of the Australian story. So, rather than being – according to Redner – an “unlikely” place for a museum, perhaps there is no better location to tell the history of the Holocaust which is at the same time both a defining event in world history but also an intensely local story, than in this “ordinary suburban street”.

Through all the changes since 1984 then, there is a continuous thread that runs through our work. The initial impetus of the founders remains. We are a place where their voices are heard in many ways, where we warn about the dangers of antisemitism and racism, and where all can come and share in the hope for a more peaceful future.